mirror of https://github.com/tiangolo/fastapi.git

699 lines

34 KiB

Markdown

699 lines

34 KiB

Markdown

# FastAPI in Containers - Docker

|

|

|

|

When deploying FastAPI applications a common approach is to build a **Linux container image**. It's normally done using <a href="https://www.docker.com/" class="external-link" target="_blank">**Docker**</a>. You can then deploy that container image in one of a few possible ways.

|

|

|

|

Using Linux containers has several advantages including **security**, **replicability**, **simplicity**, and others.

|

|

|

|

!!! tip

|

|

In a hurry and already know this stuff? Jump to the [`Dockerfile` below 👇](#build-a-docker-image-for-fastapi).

|

|

|

|

<details>

|

|

<summary>Dockerfile Preview 👀</summary>

|

|

|

|

```Dockerfile

|

|

FROM python:3.9

|

|

|

|

WORKDIR /code

|

|

|

|

COPY ./requirements.txt /code/requirements.txt

|

|

|

|

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir --upgrade -r /code/requirements.txt

|

|

|

|

COPY ./app /code/app

|

|

|

|

CMD ["uvicorn", "app.main:app", "--host", "0.0.0.0", "--port", "80"]

|

|

|

|

# If running behind a proxy like Nginx or Traefik add --proxy-headers

|

|

# CMD ["uvicorn", "app.main:app", "--host", "0.0.0.0", "--port", "80", "--proxy-headers"]

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

</details>

|

|

|

|

## What is a Container

|

|

|

|

Containers (mainly Linux containers) are a very **lightweight** way to package applications including all their dependencies and necessary files while keeping them isolated from other containers (other applications or components) in the same system.

|

|

|

|

Linux containers run using the same Linux kernel of the host (machine, virtual machine, cloud server, etc). This just means that they are very lightweight (compared to full virtual machines emulating an entire operating system).

|

|

|

|

This way, containers consume **little resources**, an amount comparable to running the processes directly (a virtual machine would consume much more).

|

|

|

|

Containers also have their own **isolated** running processes (commonly just one process), file system, and network, simplifying deployment, security, development, etc.

|

|

|

|

## What is a Container Image

|

|

|

|

A **container** is run from a **container image**.

|

|

|

|

A container image is a **static** version of all the files, environment variables, and the default command/program that should be present in a container. **Static** here means that the container **image** is not running, it's not being executed, it's only the packaged files and metadata.

|

|

|

|

In contrast to a "**container image**" that is the stored static contents, a "**container**" normally refers to the running instance, the thing that is being **executed**.

|

|

|

|

When the **container** is started and running (started from a **container image**) it could create or change files, environment variables, etc. Those changes will exist only in that container, but would not persist in the underlying container image (would not be saved to disk).

|

|

|

|

A container image is comparable to the **program** file and contents, e.g. `python` and some file `main.py`.

|

|

|

|

And the **container** itself (in contrast to the **container image**) is the actual running instance of the image, comparable to a **process**. In fact, a container is running only when it has a **process running** (and normally it's only a single process). The container stops when there's no process running in it.

|

|

|

|

## Container Images

|

|

|

|

Docker has been one of the main tools to create and manage **container images** and **containers**.

|

|

|

|

And there's a public <a href="https://hub.docker.com/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Docker Hub</a> with pre-made **official container images** for many tools, environments, databases, and applications.

|

|

|

|

For example, there's an official <a href="https://hub.docker.com/_/python" class="external-link" target="_blank">Python Image</a>.

|

|

|

|

And there are many other images for different things like databases, for example for:

|

|

|

|

* <a href="https://hub.docker.com/_/postgres" class="external-link" target="_blank">PostgreSQL</a>

|

|

* <a href="https://hub.docker.com/_/mysql" class="external-link" target="_blank">MySQL</a>

|

|

* <a href="https://hub.docker.com/_/mongo" class="external-link" target="_blank">MongoDB</a>

|

|

* <a href="https://hub.docker.com/_/redis" class="external-link" target="_blank">Redis</a>, etc.

|

|

|

|

By using a pre-made container image it's very easy to **combine** and use different tools. For example, to try out a new database. In most cases, you can use the **official images**, and just configure them with environment variables.

|

|

|

|

That way, in many cases you can learn about containers and Docker and re-use that knowledge with many different tools and components.

|

|

|

|

So, you would run **multiple containers** with different things, like a database, a Python application, a web server with a React frontend application, and connect them together via their internal network.

|

|

|

|

All the container management systems (like Docker or Kubernetes) have these networking features integrated into them.

|

|

|

|

## Containers and Processes

|

|

|

|

A **container image** normally includes in its metadata the default program or command that should be run when the **container** is started and the parameters to be passed to that program. Very similar to what would be if it was in the command line.

|

|

|

|

When a **container** is started, it will run that command/program (although you can override it and make it run a different command/program).

|

|

|

|

A container is running as long as the **main process** (command or program) is running.

|

|

|

|

A container normally has a **single process**, but it's also possible to start subprocesses from the main process, and that way you will have **multiple processes** in the same container.

|

|

|

|

But it's not possible to have a running container without **at least one running process**. If the main process stops, the container stops.

|

|

|

|

## Build a Docker Image for FastAPI

|

|

|

|

Okay, let's build something now! 🚀

|

|

|

|

I'll show you how to build a **Docker image** for FastAPI **from scratch**, based on the **official Python** image.

|

|

|

|

This is what you would want to do in **most cases**, for example:

|

|

|

|

* Using **Kubernetes** or similar tools

|

|

* When running on a **Raspberry Pi**

|

|

* Using a cloud service that would run a container image for you, etc.

|

|

|

|

### Package Requirements

|

|

|

|

You would normally have the **package requirements** for your application in some file.

|

|

|

|

It would depend mainly on the tool you use to **install** those requirements.

|

|

|

|

The most common way to do it is to have a file `requirements.txt` with the package names and their versions, one per line.

|

|

|

|

You would of course use the same ideas you read in [About FastAPI versions](./versions.md){.internal-link target=_blank} to set the ranges of versions.

|

|

|

|

For example, your `requirements.txt` could look like:

|

|

|

|

```

|

|

fastapi>=0.68.0,<0.69.0

|

|

pydantic>=1.8.0,<2.0.0

|

|

uvicorn>=0.15.0,<0.16.0

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

And you would normally install those package dependencies with `pip`, for example:

|

|

|

|

<div class="termy">

|

|

|

|

```console

|

|

$ pip install -r requirements.txt

|

|

---> 100%

|

|

Successfully installed fastapi pydantic uvicorn

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

</div>

|

|

|

|

!!! info

|

|

There are other formats and tools to define and install package dependencies.

|

|

|

|

I'll show you an example using Poetry later in a section below. 👇

|

|

|

|

### Create the **FastAPI** Code

|

|

|

|

* Create an `app` directory and enter it.

|

|

* Create an empty file `__init__.py`.

|

|

* Create a `main.py` file with:

|

|

|

|

```Python

|

|

from typing import Union

|

|

|

|

from fastapi import FastAPI

|

|

|

|

app = FastAPI()

|

|

|

|

|

|

@app.get("/")

|

|

def read_root():

|

|

return {"Hello": "World"}

|

|

|

|

|

|

@app.get("/items/{item_id}")

|

|

def read_item(item_id: int, q: Union[str, None] = None):

|

|

return {"item_id": item_id, "q": q}

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

### Dockerfile

|

|

|

|

Now in the same project directory create a file `Dockerfile` with:

|

|

|

|

```{ .dockerfile .annotate }

|

|

# (1)

|

|

FROM python:3.9

|

|

|

|

# (2)

|

|

WORKDIR /code

|

|

|

|

# (3)

|

|

COPY ./requirements.txt /code/requirements.txt

|

|

|

|

# (4)

|

|

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir --upgrade -r /code/requirements.txt

|

|

|

|

# (5)

|

|

COPY ./app /code/app

|

|

|

|

# (6)

|

|

CMD ["uvicorn", "app.main:app", "--host", "0.0.0.0", "--port", "80"]

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

1. Start from the official Python base image.

|

|

|

|

2. Set the current working directory to `/code`.

|

|

|

|

This is where we'll put the `requirements.txt` file and the `app` directory.

|

|

|

|

3. Copy the file with the requirements to the `/code` directory.

|

|

|

|

Copy **only** the file with the requirements first, not the rest of the code.

|

|

|

|

As this file **doesn't change often**, Docker will detect it and use the **cache** for this step, enabling the cache for the next step too.

|

|

|

|

4. Install the package dependencies in the requirements file.

|

|

|

|

The `--no-cache-dir` option tells `pip` to not save the downloaded packages locally, as that is only if `pip` was going to be run again to install the same packages, but that's not the case when working with containers.

|

|

|

|

!!! note

|

|

The `--no-cache-dir` is only related to `pip`, it has nothing to do with Docker or containers.

|

|

|

|

The `--upgrade` option tells `pip` to upgrade the packages if they are already installed.

|

|

|

|

Because the previous step copying the file could be detected by the **Docker cache**, this step will also **use the Docker cache** when available.

|

|

|

|

Using the cache in this step will **save** you a lot of **time** when building the image again and again during development, instead of **downloading and installing** all the dependencies **every time**.

|

|

|

|

5. Copy the `./app` directory inside the `/code` directory.

|

|

|

|

As this has all the code which is what **changes most frequently** the Docker **cache** won't be used for this or any **following steps** easily.

|

|

|

|

So, it's important to put this **near the end** of the `Dockerfile`, to optimize the container image build times.

|

|

|

|

6. Set the **command** to run the `uvicorn` server.

|

|

|

|

`CMD` takes a list of strings, each of these strings is what you would type in the command line separated by spaces.

|

|

|

|

This command will be run from the **current working directory**, the same `/code` directory you set above with `WORKDIR /code`.

|

|

|

|

Because the program will be started at `/code` and inside of it is the directory `./app` with your code, **Uvicorn** will be able to see and **import** `app` from `app.main`.

|

|

|

|

!!! tip

|

|

Review what each line does by clicking each number bubble in the code. 👆

|

|

|

|

You should now have a directory structure like:

|

|

|

|

```

|

|

.

|

|

├── app

|

|

│ ├── __init__.py

|

|

│ └── main.py

|

|

├── Dockerfile

|

|

└── requirements.txt

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

#### Behind a TLS Termination Proxy

|

|

|

|

If you are running your container behind a TLS Termination Proxy (load balancer) like Nginx or Traefik, add the option `--proxy-headers`, this will tell Uvicorn to trust the headers sent by that proxy telling it that the application is running behind HTTPS, etc.

|

|

|

|

```Dockerfile

|

|

CMD ["uvicorn", "app.main:app", "--proxy-headers", "--host", "0.0.0.0", "--port", "80"]

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

#### Docker Cache

|

|

|

|

There's an important trick in this `Dockerfile`, we first copy the **file with the dependencies alone**, not the rest of the code. Let me tell you why is that.

|

|

|

|

```Dockerfile

|

|

COPY ./requirements.txt /code/requirements.txt

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

Docker and other tools **build** these container images **incrementally**, adding **one layer on top of the other**, starting from the top of the `Dockerfile` and adding any files created by each of the instructions of the `Dockerfile`.

|

|

|

|

Docker and similar tools also use an **internal cache** when building the image, if a file hasn't changed since the last time building the container image, then it will **re-use the same layer** created the last time, instead of copying the file again and creating a new layer from scratch.

|

|

|

|

Just avoiding the copy of files doesn't necessarily improve things too much, but because it used the cache for that step, it can **use the cache for the next step**. For example, it could use the cache for the instruction that installs dependencies with:

|

|

|

|

```Dockerfile

|

|

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir --upgrade -r /code/requirements.txt

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

The file with the package requirements **won't change frequently**. So, by copying only that file, Docker will be able to **use the cache** for that step.

|

|

|

|

And then, Docker will be able to **use the cache for the next step** that downloads and install those dependencies. And here's where we **save a lot of time**. ✨ ...and avoid boredom waiting. 😪😆

|

|

|

|

Downloading and installing the package dependencies **could take minutes**, but using the **cache** would **take seconds** at most.

|

|

|

|

And as you would be building the container image again and again during development to check that your code changes are working, there's a lot of accumulated time this would save.

|

|

|

|

Then, near the end of the `Dockerfile`, we copy all the code. As this is what **changes most frequently**, we put it near the end, because almost always, anything after this step will not be able to use the cache.

|

|

|

|

```Dockerfile

|

|

COPY ./app /code/app

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

### Build the Docker Image

|

|

|

|

Now that all the files are in place, let's build the container image.

|

|

|

|

* Go to the project directory (in where your `Dockerfile` is, containing your `app` directory).

|

|

* Build your FastAPI image:

|

|

|

|

<div class="termy">

|

|

|

|

```console

|

|

$ docker build -t myimage .

|

|

|

|

---> 100%

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

</div>

|

|

|

|

!!! tip

|

|

Notice the `.` at the end, it's equivalent to `./`, it tells Docker the directory to use to build the container image.

|

|

|

|

In this case, it's the same current directory (`.`).

|

|

|

|

### Start the Docker Container

|

|

|

|

* Run a container based on your image:

|

|

|

|

<div class="termy">

|

|

|

|

```console

|

|

$ docker run -d --name mycontainer -p 80:80 myimage

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

</div>

|

|

|

|

## Check it

|

|

|

|

You should be able to check it in your Docker container's URL, for example: <a href="http://192.168.99.100/items/5?q=somequery" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://192.168.99.100/items/5?q=somequery</a> or <a href="http://127.0.0.1/items/5?q=somequery" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1/items/5?q=somequery</a> (or equivalent, using your Docker host).

|

|

|

|

You will see something like:

|

|

|

|

```JSON

|

|

{"item_id": 5, "q": "somequery"}

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

## Interactive API docs

|

|

|

|

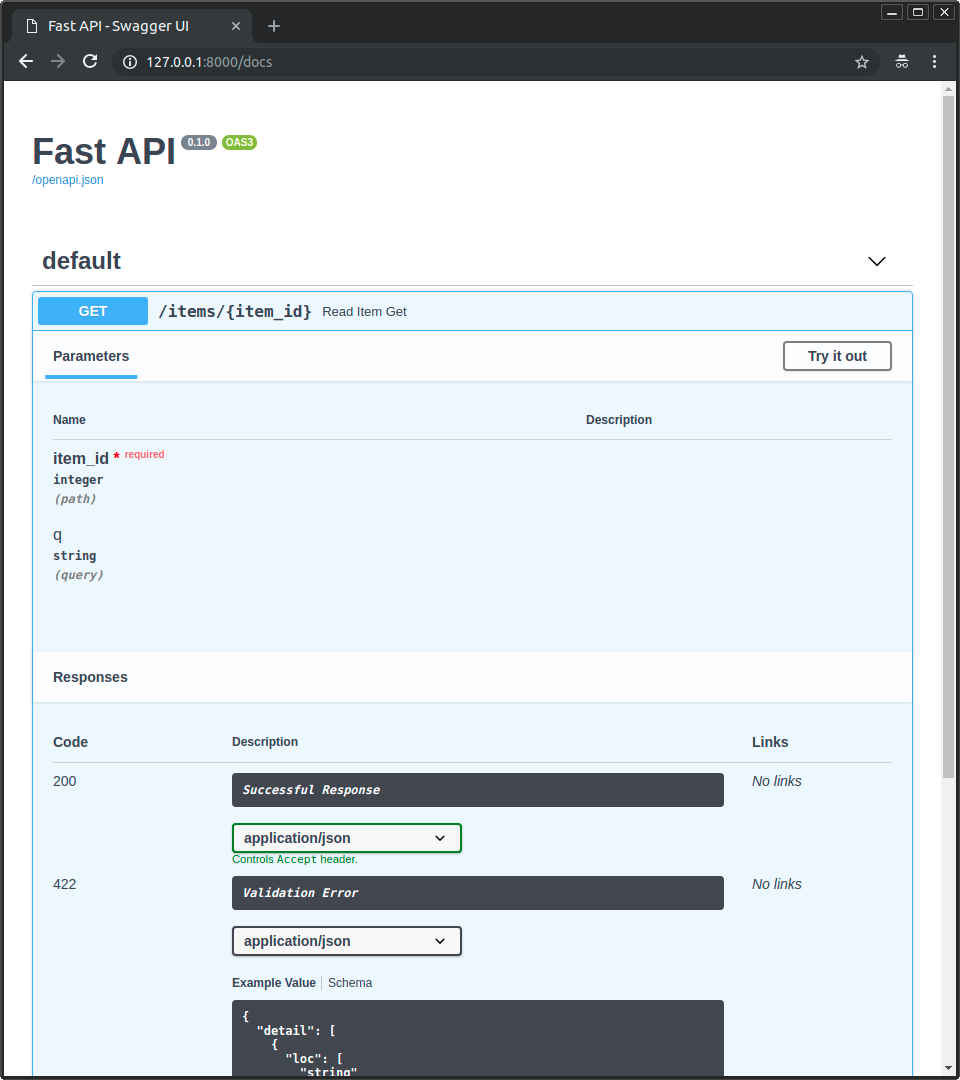

Now you can go to <a href="http://192.168.99.100/docs" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://192.168.99.100/docs</a> or <a href="http://127.0.0.1/docs" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1/docs</a> (or equivalent, using your Docker host).

|

|

|

|

You will see the automatic interactive API documentation (provided by <a href="https://github.com/swagger-api/swagger-ui" class="external-link" target="_blank">Swagger UI</a>):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

## Alternative API docs

|

|

|

|

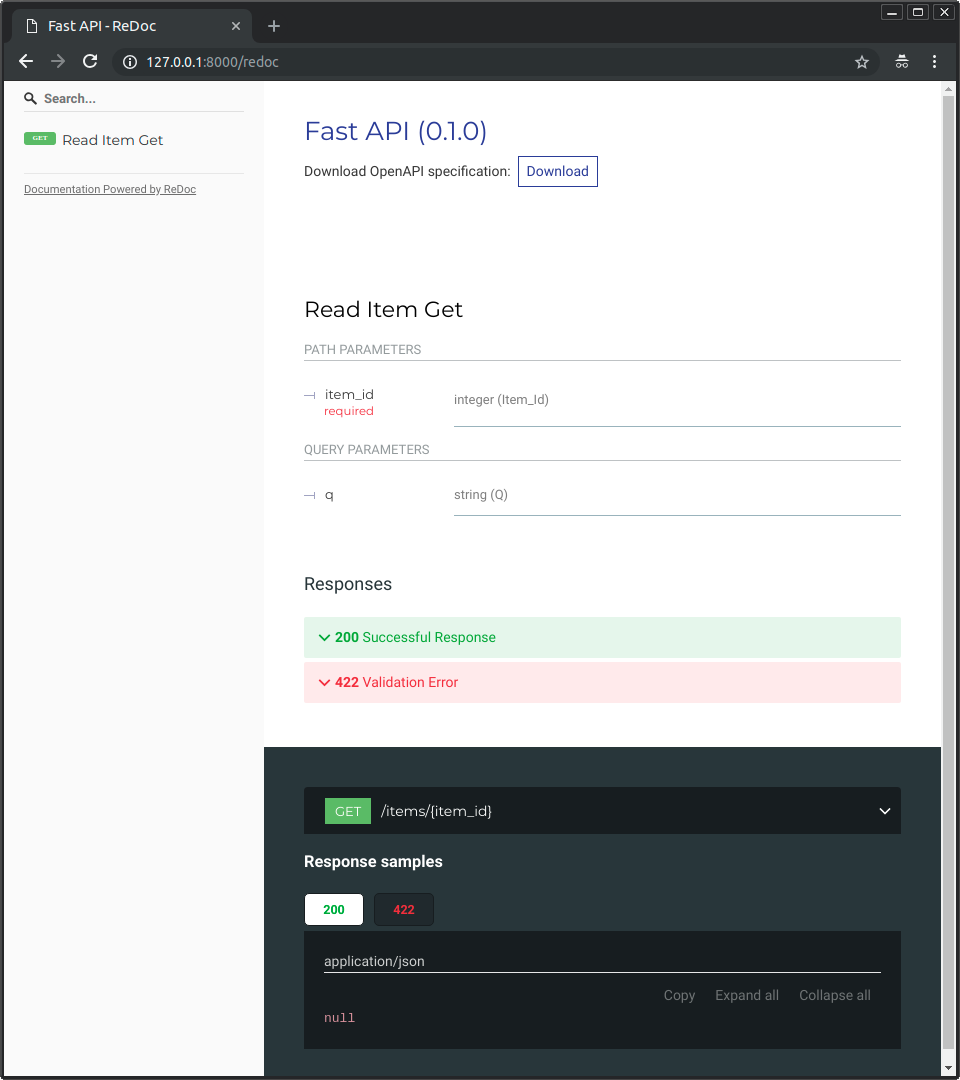

And you can also go to <a href="http://192.168.99.100/redoc" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://192.168.99.100/redoc</a> or <a href="http://127.0.0.1/redoc" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1/redoc</a> (or equivalent, using your Docker host).

|

|

|

|

You will see the alternative automatic documentation (provided by <a href="https://github.com/Rebilly/ReDoc" class="external-link" target="_blank">ReDoc</a>):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

## Build a Docker Image with a Single-File FastAPI

|

|

|

|

If your FastAPI is a single file, for example, `main.py` without an `./app` directory, your file structure could look like this:

|

|

|

|

```

|

|

.

|

|

├── Dockerfile

|

|

├── main.py

|

|

└── requirements.txt

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

Then you would just have to change the corresponding paths to copy the file inside the `Dockerfile`:

|

|

|

|

```{ .dockerfile .annotate hl_lines="10 13" }

|

|

FROM python:3.9

|

|

|

|

WORKDIR /code

|

|

|

|

COPY ./requirements.txt /code/requirements.txt

|

|

|

|

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir --upgrade -r /code/requirements.txt

|

|

|

|

# (1)

|

|

COPY ./main.py /code/

|

|

|

|

# (2)

|

|

CMD ["uvicorn", "main:app", "--host", "0.0.0.0", "--port", "80"]

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

1. Copy the `main.py` file to the `/code` directory directly (without any `./app` directory).

|

|

|

|

2. Run Uvicorn and tell it to import the `app` object from `main` (instead of importing from `app.main`).

|

|

|

|

Then adjust the Uvicorn command to use the new module `main` instead of `app.main` to import the FastAPI object `app`.

|

|

|

|

## Deployment Concepts

|

|

|

|

Let's talk again about some of the same [Deployment Concepts](./concepts.md){.internal-link target=_blank} in terms of containers.

|

|

|

|

Containers are mainly a tool to simplify the process of **building and deploying** an application, but they don't enforce a particular approach to handle these **deployment concepts**, and there are several possible strategies.

|

|

|

|

The **good news** is that with each different strategy there's a way to cover all of the deployment concepts. 🎉

|

|

|

|

Let's review these **deployment concepts** in terms of containers:

|

|

|

|

* HTTPS

|

|

* Running on startup

|

|

* Restarts

|

|

* Replication (the number of processes running)

|

|

* Memory

|

|

* Previous steps before starting

|

|

|

|

## HTTPS

|

|

|

|

If we focus just on the **container image** for a FastAPI application (and later the running **container**), HTTPS normally would be handled **externally** by another tool.

|

|

|

|

It could be another container, for example with <a href="https://traefik.io/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Traefik</a>, handling **HTTPS** and **automatic** acquisition of **certificates**.

|

|

|

|

!!! tip

|

|

Traefik has integrations with Docker, Kubernetes, and others, so it's very easy to set up and configure HTTPS for your containers with it.

|

|

|

|

Alternatively, HTTPS could be handled by a cloud provider as one of their services (while still running the application in a container).

|

|

|

|

## Running on Startup and Restarts

|

|

|

|

There is normally another tool in charge of **starting and running** your container.

|

|

|

|

It could be **Docker** directly, **Docker Compose**, **Kubernetes**, a **cloud service**, etc.

|

|

|

|

In most (or all) cases, there's a simple option to enable running the container on startup and enabling restarts on failures. For example, in Docker, it's the command line option `--restart`.

|

|

|

|

Without using containers, making applications run on startup and with restarts can be cumbersome and difficult. But when **working with containers** in most cases that functionality is included by default. ✨

|

|

|

|

## Replication - Number of Processes

|

|

|

|

If you have a <abbr title="A group of machines that are configured to be connected and work together in some way.">cluster</abbr> of machines with **Kubernetes**, Docker Swarm Mode, Nomad, or another similar complex system to manage distributed containers on multiple machines, then you will probably want to **handle replication** at the **cluster level** instead of using a **process manager** (like Gunicorn with workers) in each container.

|

|

|

|

One of those distributed container management systems like Kubernetes normally has some integrated way of handling **replication of containers** while still supporting **load balancing** for the incoming requests. All at the **cluster level**.

|

|

|

|

In those cases, you would probably want to build a **Docker image from scratch** as [explained above](#dockerfile), installing your dependencies, and running **a single Uvicorn process** instead of running something like Gunicorn with Uvicorn workers.

|

|

|

|

### Load Balancer

|

|

|

|

When using containers, you would normally have some component **listening on the main port**. It could possibly be another container that is also a **TLS Termination Proxy** to handle **HTTPS** or some similar tool.

|

|

|

|

As this component would take the **load** of requests and distribute that among the workers in a (hopefully) **balanced** way, it is also commonly called a **Load Balancer**.

|

|

|

|

!!! tip

|

|

The same **TLS Termination Proxy** component used for HTTPS would probably also be a **Load Balancer**.

|

|

|

|

And when working with containers, the same system you use to start and manage them would already have internal tools to transmit the **network communication** (e.g. HTTP requests) from that **load balancer** (that could also be a **TLS Termination Proxy**) to the container(s) with your app.

|

|

|

|

### One Load Balancer - Multiple Worker Containers

|

|

|

|

When working with **Kubernetes** or similar distributed container management systems, using their internal networking mechanisms would allow the single **load balancer** that is listening on the main **port** to transmit communication (requests) to possibly **multiple containers** running your app.

|

|

|

|

Each of these containers running your app would normally have **just one process** (e.g. a Uvicorn process running your FastAPI application). They would all be **identical containers**, running the same thing, but each with its own process, memory, etc. That way you would take advantage of **parallelization** in **different cores** of the CPU, or even in **different machines**.

|

|

|

|

And the distributed container system with the **load balancer** would **distribute the requests** to each one of the containers with your app **in turns**. So, each request could be handled by one of the multiple **replicated containers** running your app.

|

|

|

|

And normally this **load balancer** would be able to handle requests that go to *other* apps in your cluster (e.g. to a different domain, or under a different URL path prefix), and would transmit that communication to the right containers for *that other* application running in your cluster.

|

|

|

|

### One Process per Container

|

|

|

|

In this type of scenario, you probably would want to have **a single (Uvicorn) process per container**, as you would already be handling replication at the cluster level.

|

|

|

|

So, in this case, you **would not** want to have a process manager like Gunicorn with Uvicorn workers, or Uvicorn using its own Uvicorn workers. You would want to have just a **single Uvicorn process** per container (but probably multiple containers).

|

|

|

|

Having another process manager inside the container (as would be with Gunicorn or Uvicorn managing Uvicorn workers) would only add **unnecessary complexity** that you are most probably already taking care of with your cluster system.

|

|

|

|

### Containers with Multiple Processes and Special Cases

|

|

|

|

Of course, there are **special cases** where you could want to have **a container** with a **Gunicorn process manager** starting several **Uvicorn worker processes** inside.

|

|

|

|

In those cases, you can use the **official Docker image** that includes **Gunicorn** as a process manager running multiple **Uvicorn worker processes**, and some default settings to adjust the number of workers based on the current CPU cores automatically. I'll tell you more about it below in [Official Docker Image with Gunicorn - Uvicorn](#official-docker-image-with-gunicorn-uvicorn).

|

|

|

|

Here are some examples of when that could make sense:

|

|

|

|

#### A Simple App

|

|

|

|

You could want a process manager in the container if your application is **simple enough** that you don't need (at least not yet) to fine-tune the number of processes too much, and you can just use an automated default (with the official Docker image), and you are running it on a **single server**, not a cluster.

|

|

|

|

#### Docker Compose

|

|

|

|

You could be deploying to a **single server** (not a cluster) with **Docker Compose**, so you wouldn't have an easy way to manage replication of containers (with Docker Compose) while preserving the shared network and **load balancing**.

|

|

|

|

Then you could want to have **a single container** with a **process manager** starting **several worker processes** inside.

|

|

|

|

#### Prometheus and Other Reasons

|

|

|

|

You could also have **other reasons** that would make it easier to have a **single container** with **multiple processes** instead of having **multiple containers** with **a single process** in each of them.

|

|

|

|

For example (depending on your setup) you could have some tool like a Prometheus exporter in the same container that should have access to **each of the requests** that come.

|

|

|

|

In this case, if you had **multiple containers**, by default, when Prometheus came to **read the metrics**, it would get the ones for **a single container each time** (for the container that handled that particular request), instead of getting the **accumulated metrics** for all the replicated containers.

|

|

|

|

Then, in that case, it could be simpler to have **one container** with **multiple processes**, and a local tool (e.g. a Prometheus exporter) on the same container collecting Prometheus metrics for all the internal processes and exposing those metrics on that single container.

|

|

|

|

---

|

|

|

|

The main point is, **none** of these are **rules written in stone** that you have to blindly follow. You can use these ideas to **evaluate your own use case** and decide what is the best approach for your system, checking out how to manage the concepts of:

|

|

|

|

* Security - HTTPS

|

|

* Running on startup

|

|

* Restarts

|

|

* Replication (the number of processes running)

|

|

* Memory

|

|

* Previous steps before starting

|

|

|

|

## Memory

|

|

|

|

If you run **a single process per container** you will have a more or less well-defined, stable, and limited amount of memory consumed by each of those containers (more than one if they are replicated).

|

|

|

|

And then you can set those same memory limits and requirements in your configurations for your container management system (for example in **Kubernetes**). That way it will be able to **replicate the containers** in the **available machines** taking into account the amount of memory needed by them, and the amount available in the machines in the cluster.

|

|

|

|

If your application is **simple**, this will probably **not be a problem**, and you might not need to specify hard memory limits. But if you are **using a lot of memory** (for example with **machine learning** models), you should check how much memory you are consuming and adjust the **number of containers** that runs in **each machine** (and maybe add more machines to your cluster).

|

|

|

|

If you run **multiple processes per container** (for example with the official Docker image) you will have to make sure that the number of processes started doesn't **consume more memory** than what is available.

|

|

|

|

## Previous Steps Before Starting and Containers

|

|

|

|

If you are using containers (e.g. Docker, Kubernetes), then there are two main approaches you can use.

|

|

|

|

### Multiple Containers

|

|

|

|

If you have **multiple containers**, probably each one running a **single process** (for example, in a **Kubernetes** cluster), then you would probably want to have a **separate container** doing the work of the **previous steps** in a single container, running a single process, **before** running the replicated worker containers.

|

|

|

|

!!! info

|

|

If you are using Kubernetes, this would probably be an <a href="https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/workloads/pods/init-containers/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Init Container</a>.

|

|

|

|

If in your use case there's no problem in running those previous steps **multiple times in parallel** (for example if you are not running database migrations, but just checking if the database is ready yet), then you could also just put them in each container right before starting the main process.

|

|

|

|

### Single Container

|

|

|

|

If you have a simple setup, with a **single container** that then starts multiple **worker processes** (or also just one process), then you could run those previous steps in the same container, right before starting the process with the app. The official Docker image supports this internally.

|

|

|

|

## Official Docker Image with Gunicorn - Uvicorn

|

|

|

|

There is an official Docker image that includes Gunicorn running with Uvicorn workers, as detailed in a previous chapter: [Server Workers - Gunicorn with Uvicorn](./server-workers.md){.internal-link target=_blank}.

|

|

|

|

This image would be useful mainly in the situations described above in: [Containers with Multiple Processes and Special Cases](#containers-with-multiple-processes-and-special-cases).

|

|

|

|

* <a href="https://github.com/tiangolo/uvicorn-gunicorn-fastapi-docker" class="external-link" target="_blank">tiangolo/uvicorn-gunicorn-fastapi</a>.

|

|

|

|

!!! warning

|

|

There's a high chance that you **don't** need this base image or any other similar one, and would be better off by building the image from scratch as [described above in: Build a Docker Image for FastAPI](#build-a-docker-image-for-fastapi).

|

|

|

|

This image has an **auto-tuning** mechanism included to set the **number of worker processes** based on the CPU cores available.

|

|

|

|

It has **sensible defaults**, but you can still change and update all the configurations with **environment variables** or configuration files.

|

|

|

|

It also supports running <a href="https://github.com/tiangolo/uvicorn-gunicorn-fastapi-docker#pre_start_path" class="external-link" target="_blank">**previous steps before starting**</a> with a script.

|

|

|

|

!!! tip

|

|

To see all the configurations and options, go to the Docker image page: <a href="https://github.com/tiangolo/uvicorn-gunicorn-fastapi-docker" class="external-link" target="_blank">tiangolo/uvicorn-gunicorn-fastapi</a>.

|

|

|

|

### Number of Processes on the Official Docker Image

|

|

|

|

The **number of processes** on this image is **computed automatically** from the CPU **cores** available.

|

|

|

|

This means that it will try to **squeeze** as much **performance** from the CPU as possible.

|

|

|

|

You can also adjust it with the configurations using **environment variables**, etc.

|

|

|

|

But it also means that as the number of processes depends on the CPU the container is running, the **amount of memory consumed** will also depend on that.

|

|

|

|

So, if your application consumes a lot of memory (for example with machine learning models), and your server has a lot of CPU cores **but little memory**, then your container could end up trying to use more memory than what is available, and degrading performance a lot (or even crashing). 🚨

|

|

|

|

### Create a `Dockerfile`

|

|

|

|

Here's how you would create a `Dockerfile` based on this image:

|

|

|

|

```Dockerfile

|

|

FROM tiangolo/uvicorn-gunicorn-fastapi:python3.9

|

|

|

|

COPY ./requirements.txt /app/requirements.txt

|

|

|

|

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir --upgrade -r /app/requirements.txt

|

|

|

|

COPY ./app /app

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

### Bigger Applications

|

|

|

|

If you followed the section about creating [Bigger Applications with Multiple Files](../tutorial/bigger-applications.md){.internal-link target=_blank}, your `Dockerfile` might instead look like:

|

|

|

|

```Dockerfile hl_lines="7"

|

|

FROM tiangolo/uvicorn-gunicorn-fastapi:python3.9

|

|

|

|

COPY ./requirements.txt /app/requirements.txt

|

|

|

|

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir --upgrade -r /app/requirements.txt

|

|

|

|

COPY ./app /app/app

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

### When to Use

|

|

|

|

You should probably **not** use this official base image (or any other similar one) if you are using **Kubernetes** (or others) and you are already setting **replication** at the cluster level, with multiple **containers**. In those cases, you are better off **building an image from scratch** as described above: [Build a Docker Image for FastAPI](#build-a-docker-image-for-fastapi).

|

|

|

|

This image would be useful mainly in the special cases described above in [Containers with Multiple Processes and Special Cases](#containers-with-multiple-processes-and-special-cases). For example, if your application is **simple enough** that setting a default number of processes based on the CPU works well, you don't want to bother with manually configuring the replication at the cluster level, and you are not running more than one container with your app. Or if you are deploying with **Docker Compose**, running on a single server, etc.

|

|

|

|

## Deploy the Container Image

|

|

|

|

After having a Container (Docker) Image there are several ways to deploy it.

|

|

|

|

For example:

|

|

|

|

* With **Docker Compose** in a single server

|

|

* With a **Kubernetes** cluster

|

|

* With a Docker Swarm Mode cluster

|

|

* With another tool like Nomad

|

|

* With a cloud service that takes your container image and deploys it

|

|

|

|

## Docker Image with Poetry

|

|

|

|

If you use <a href="https://python-poetry.org/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Poetry</a> to manage your project's dependencies, you could use Docker multi-stage building:

|

|

|

|

```{ .dockerfile .annotate }

|

|

# (1)

|

|

FROM python:3.9 as requirements-stage

|

|

|

|

# (2)

|

|

WORKDIR /tmp

|

|

|

|

# (3)

|

|

RUN pip install poetry

|

|

|

|

# (4)

|

|

COPY ./pyproject.toml ./poetry.lock* /tmp/

|

|

|

|

# (5)

|

|

RUN poetry export -f requirements.txt --output requirements.txt --without-hashes

|

|

|

|

# (6)

|

|

FROM python:3.9

|

|

|

|

# (7)

|

|

WORKDIR /code

|

|

|

|

# (8)

|

|

COPY --from=requirements-stage /tmp/requirements.txt /code/requirements.txt

|

|

|

|

# (9)

|

|

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir --upgrade -r /code/requirements.txt

|

|

|

|

# (10)

|

|

COPY ./app /code/app

|

|

|

|

# (11)

|

|

CMD ["uvicorn", "app.main:app", "--host", "0.0.0.0", "--port", "80"]

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

1. This is the first stage, it is named `requirements-stage`.

|

|

|

|

2. Set `/tmp` as the current working directory.

|

|

|

|

Here's where we will generate the file `requirements.txt`

|

|

|

|

3. Install Poetry in this Docker stage.

|

|

|

|

4. Copy the `pyproject.toml` and `poetry.lock` files to the `/tmp` directory.

|

|

|

|

Because it uses `./poetry.lock*` (ending with a `*`), it won't crash if that file is not available yet.

|

|

|

|

5. Generate the `requirements.txt` file.

|

|

|

|

6. This is the final stage, anything here will be preserved in the final container image.

|

|

|

|

7. Set the current working directory to `/code`.

|

|

|

|

8. Copy the `requirements.txt` file to the `/code` directory.

|

|

|

|

This file only lives in the previous Docker stage, that's why we use `--from-requirements-stage` to copy it.

|

|

|

|

9. Install the package dependencies in the generated `requirements.txt` file.

|

|

|

|

10. Copy the `app` directory to the `/code` directory.

|

|

|

|

11. Run the `uvicorn` command, telling it to use the `app` object imported from `app.main`.

|

|

|

|

!!! tip

|

|

Click the bubble numbers to see what each line does.

|

|

|

|

A **Docker stage** is a part of a `Dockerfile` that works as a **temporary container image** that is only used to generate some files to be used later.

|

|

|

|

The first stage will only be used to **install Poetry** and to **generate the `requirements.txt`** with your project dependencies from Poetry's `pyproject.toml` file.

|

|

|

|

This `requirements.txt` file will be used with `pip` later in the **next stage**.

|

|

|

|

In the final container image **only the final stage** is preserved. The previous stage(s) will be discarded.

|

|

|

|

When using Poetry, it would make sense to use **Docker multi-stage builds** because you don't really need to have Poetry and its dependencies installed in the final container image, you **only need** to have the generated `requirements.txt` file to install your project dependencies.

|

|

|

|

Then in the next (and final) stage you would build the image more or less in the same way as described before.

|

|

|

|

### Behind a TLS Termination Proxy - Poetry

|

|

|

|

Again, if you are running your container behind a TLS Termination Proxy (load balancer) like Nginx or Traefik, add the option `--proxy-headers` to the command:

|

|

|

|

```Dockerfile

|

|

CMD ["uvicorn", "app.main:app", "--proxy-headers", "--host", "0.0.0.0", "--port", "80"]

|

|

```

|

|

|

|

## Recap

|

|

|

|

Using container systems (e.g. with **Docker** and **Kubernetes**) it becomes fairly straightforward to handle all the **deployment concepts**:

|

|

|

|

* HTTPS

|

|

* Running on startup

|

|

* Restarts

|

|

* Replication (the number of processes running)

|

|

* Memory

|

|

* Previous steps before starting

|

|

|

|

In most cases, you probably won't want to use any base image, and instead **build a container image from scratch** one based on the official Python Docker image.

|

|

|

|

Taking care of the **order** of instructions in the `Dockerfile` and the **Docker cache** you can **minimize build times**, to maximize your productivity (and avoid boredom). 😎

|

|

|

|

In certain special cases, you might want to use the official Docker image for FastAPI. 🤓

|